2024.10.14

Cultivating Tomorrow #3

Conversation with AAWAA

All in Sync

When I introduce myself as a writer, I doubt anyone wonders which means of creative expression I’d use. However, it’d be a shame if that automatically crossed out other possibilities I may employ in my creation. As the writer Elizabeth Gilbert suggests in her writing, every single act we decide to take in our everyday life is a creative act.

Plying threads, making clothings, producing spaces, and writing… AAWAA utilizes and combines endless options of creative expressions to create artworks in TOMORROW FIELD. “Ni”, his work published in 2023, reenacts the ancient conscience hidden deep in the land of Tango, Kyoto, seen from his contemporary, unique perspective.

He has been engaged in wide-ranged forms of creative expression, including clothing at Cosmic Wonder, space design and production in a gallery. His new works, intersecting with his trajectory, embrace soft and fluid boundaries of creation.

The third edition of the interview series “Cultivating Tomorrow” offers an in-depth opportunity to delve into his creative and thought process behind the works that derived from the study of ancient methods and forgotten crafts, as well as the procedures that bring them to life today.

The interview with AAWAA took place at the TAIZA studio, joined by Natsuka Okamoto, Artist Liezon from TOMORROW FIELD. Okamoto has also been managing contemporary artists, including AAWAA, at an art gallery.

Encounter

When did you first meet TOMORROW FIELD?

AAWAA/Maeda (A): It was just after I moved to an area called Miyama-cho, Nantan City, in Kyoto, about 10 years ago. I decided to live in an old house with a thatched-roof in the Important Preservation District for Groups of Traditional Buildings. There, I actively took part in the renovation process, with professional help from carpenters and plasterers.

I then became interested in the entire ecosystem of the land and the surrounding mountains, and I started inviting people from the villagers and experts to discuss the possibility of restoration of the old landscape of the area. It was around this time that Kayo Tokuda and Shunya Hashizume from NPO TOMORROW came to visit me in Ryugu (AAWAA’s atelier /home, translates as Dragon King’s Palace) with Okamoto san.

Natsuka Okamoto (O): He made us a delicious lunch; onigiri -rice balls, soup, and pickles, all homemade. His house was being renovated by himself, and every little thing in his house, from the books he reads, the objects scattered around the space, to the hospitality he provided, was the embodiment of who he was. It left us with such a strong impression.

Although we were still in the preliminary stage of building the concept for the community project by the sea, where art and life seamlessly coexist, we were able to touch upon the same philosophy expressed through his act of living. There was an instant resonance we felt.

In my previous interview with Tokuda san, she spoke of the importance of holistic presentation of surroundings: having one piece of great work hanging on a wall isn’t enough and it has to come in harmony with the experience of entering and feeling the entire space. Likewise in TOMORROW FIELD, every food, dish and utensil to serve the food, all have to express the same vision. And what you, Maeda san, were doing there was precisely the embodiment of that vision.

A:Yes, that was probably right.

Creative Process

From the moment you met, did you have some sense of direction as to what you were going to make in Taiza?

A: No. We started with very little being decided. There was no specific instruction from Tokuda san either. What we did was to keep the conversation going. Through the repeated process of asking each other “What do you want to do?” and discovering what speaks to each of us, we slowly became aligned with the vision of where we’d like to go.

Where do you receive inspiration for your work usually?

A: It depends. Sometimes a discovery of material ignites everything. For example, I once found a coastal plant called Hamagou which smelled like sage while strolling on Kotohiki beach. I just loved its fragrance and appearance. And that was enough to get me started on the research.

I collected leaves and seeds. As I researched, I learned the plant was used for aromatic pillows and so on in the Heian period (794-1185). I became more and more interested in both the material and its historical background, which eventually led me to create a work* that incorporated these elements.

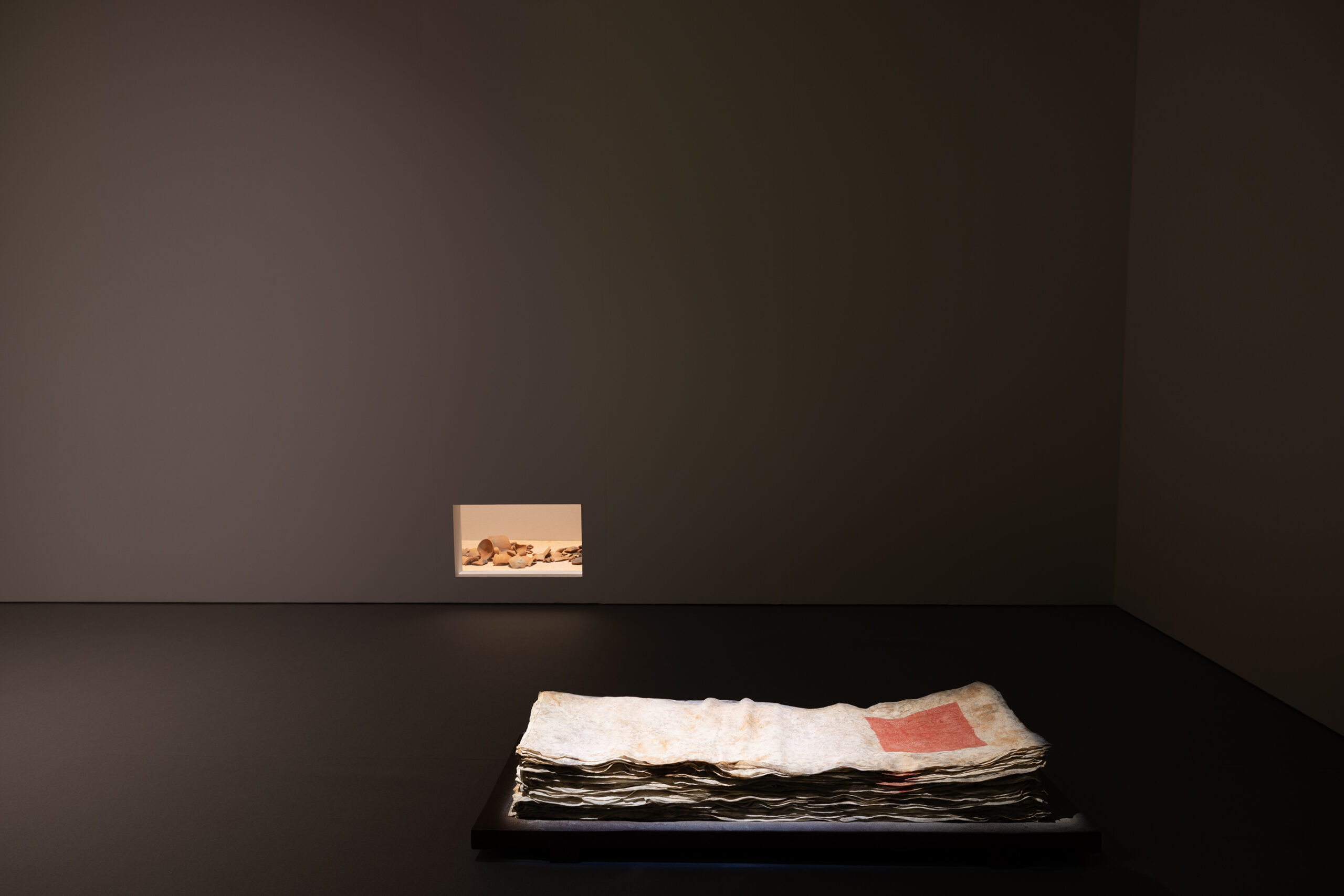

AAWAA "Ni" 2023 Photo: Ai Nakagawa

Last year for TOMORROW FIELD, you presented the piece “Ni”, which incorporated the local red soil from Taiza. I learnt that the character 丹 (ni /tan) meant “red.” Would you tell us how this came to be?

A: Nantan City, where I live, also has the character 丹 in its name. The reason for that is because the area produced red soil and cinnabar for a long time. And the same geological feature covered quite a wide area, extending from my city to around here.

A friend of mine who lives close by often complains that his water pipe gets rusty and the water turns red, as he draws well water into the pipeline. So I was already familiar with these geological features of the area, and was interested in exploring the soil and iron, which is the source of the color.

It was around that time that I visited the Tango Ancient Village Museum as part of my research. There I was shown cinnabar sand which was excavated from a tomb from the Yayoi period (ca. 300 B.C. ~ 300 A.D.). It used to be in a wooden coffin which belonged to a person of presumably the ruling class, and the cinnabar was considered to have been applied beneath the person’s head. Red symbolizes life, and it may have meant the life force offered to the deceased or a wish for resurrection.

It was fortunate for us to witness the cinnabar just as it was dug out. The vivid presence of the soil, which must have captivated the ancient people in the same way, was striking.

O: The freshness, rawness, and lush colors all left us mesmerized.

A: That was the moment when the idea came to us to do something with cinnabar and red soil.

O: There is a shrine in Taiza, called Niu Shrine. It is spelt 丹生: the place where red is born. The name itself tells a story of the land that it used to produce cinnabar.

A: Whether it was water or cinnabar, things that people cherished were often remembered in such ways and are still present in our daily life today.

AAWAA "Ni" 2023 Photo: Ai Nakagawa

A: I was also researching Tango silk. I heard that silk has been around since the Yayoi period. I assumed that the people of the class, who were buried in the tombs, would have worn those silk clothes. We thought of soil-dyeing the silk fabric woven by one of the traditional silk producers. We created something that looked like a box, or a coffin, which consisted of layered silk fabric, and buried the lump underground. That became the art piece “Ni” in 2023.

Each work we present is a fruit of various research coming together. The work “Ni” showcased the first stage, which will lead to this year’s artwork.

AAWAA "Ni" 2023 Photo: Noboru Morikawa

That leads us to your 2024 production. What kind of scenery unfolds in front of you now?

A: We are currently working on the ancient textile –fujifu– which was preserved around here until very recently. It is a fabric woven with extracted wisteria fibers, a technique that was practiced all over Japan for a long time. The origin of the textile dates back to the Jomon period (ca. 14,000 B.C. ~ 300 B.C.).

There is also an ancient weaving technique called ootsuzure in Japan. It is a fabric woven with wisteria thread, each of which is wrapped with washi Japanese paper. There are various theories for why it’s done in such ways: some say that the Japanese paper brightens the color, making it look like a white cloth; others say the paper softens the surface and keeps the warmth. Taking inspiration from this ancient technique, we are trying to create what could be called a modern version of the ootsuzure with a method we invented.

I took reference from the papermaking method. Imagine the square frame for the papermaking, and a sheet of beams to be set in the frame. We made the beams with wisteria fiber. And instead of pulp, we used liquified silk which had been soil-dyed, and added kozo -mulberry tree and cinnabar from Tango. When we scoop up the mixture with the frame, there we get the wisteria fiber coated with silk and all other ingredients. The ancient wisteria fiber from the Jomon period is coated with silk, which was worn by the rulers in the Yayoi period.

AAWAA "Ni" 2023 Photo: Noboru Morikawa

Burying, painting, and mixing it with papermaking method… You are experimenting with various ways to utilize local materials.

A: That’s right. We’re creating something with what we can procure locally. No one has ever done this kind of work before, so it is all done by trial and error.

There are unimaginable processes just to extract the wisteria fibers. Then, the mixture of silk, mulberry and cinnabar is applied to the thread. It’s all been made possible thanks to Hikoro Sakane, the fujifu weaver, and Ayumi Oe, the paper maker. They willingly took on this challenging and time-consuming work. I don’t think it’s the kind of work anyone could do. Therefore, it truly is a blessing to meet a maker who cares and sees the values in the work we do. It is amazing to have such encounters here in Tango, and to be able to do both research and production.

AAWAA is born

Where does the name AAWAA come from?

A: I have been writing for some time, and I used the pen name AAWAA, picked pretty randomly, so that no one would know who had written it. And the name started to feel right to me. It’s not that I wanted anonymity, but I suppose it was something similar to that.

Talking of anonymity, it reminds me of craftspeople’s attitude towards crafts. Many describe their creation to be the product of nature, environment and ancestors, not just their own efforts. Is it similar to what you were just describing?

A: It wouldn’t go to that extent. After all, it is born under my name and supervision.

O: What it suggests is… It may symbolize new way of creative, artistic expression, which resonates with TOMORROW FIELD’s philosophy. For example, the conventional way to build a studio like this is to call in a famous architect to draft a complete plan. However, in TOMORROW FIELD, all sorts of people, like artists, craftspeople, and cooks, work together and the project starts taking its shape somehow like pieces of a puzzle put together. So all of the participants’ names are lined up in the same way. Some people may be confused by this style at first. But it is a crucial part of what we are about, that everyone is equally a member of the project.

Similarly, Maeda san also creates work communicating with many people, and his attitude is never about putting only his name out there. I remember it was 2023 when he requested to present his works as AAWAA’s. There was the era of artist Maeda, and now, after 10 or 20 years of maturation, AAWAA is here. The name AAWAA has an element of anonymity, but also it is an expression of the fact that so many people are involved in this project. It represents his unique way of being an artist. I just understood that now hearing what you said.

A: I think you just clarified it for me.

*

“kami”

COSMIC WONDER with Kogei Punks Sha

Exhibition at SHISEIDO GALLERY, 2017

Interview/Translation: Tomo Yoshizawa (Cultural Translator)