2025.6.4

Cultivating Tomorrow #4

Conversation with Koh Kado (Kamisoe)

Shifting Perspective, Clarifying Contour

Koh Kado spent much of his childhood and youth in Kyoto, before leaving for the United States to study graphic design, eventually landing a position at a design firm in New York. There, surrounded by cutting-edge techniques and the latest technology —everything he had once dreamed of— Kado also found himself unexpectedly drawn to something else: the scent from a letterpress studio he popped in one day, and the sight of artisans working with their entire bodies.

Upon returning to Japan, Kado began his training as a karakami craftsman -traditional wood block printing on washi paper- at a Kyoto-based studio with over 400 years of history. In 2009, he established his own studio and shop, Kamisoe, housed in a former barbershop nestled in Kyoto’s Nishijin district.

Today, his practice ranges widely—from restoring fusuma (sliding doors) in temples and shrines to collaborating with contemporary artists. He’s also the first craftsperson Kayo Tokuda, the NPO TOMORROW founder, has worked with since she moved to Kyoto.

We visited Kamisoe with Shunya Hashizume, a core member of TOMORROW FIELD. There, we were struck by Kado’s clarity of vision in his craft, and how his perspective extends far, reaching toward the horizon of TOMORROW FIELD.

Encounter at a Hot Spring

I heard that Tokuda-san met you soon after moving to Kyoto.

She picked me for one of her first projects after coming to Kyoto. At that time, Kamisoe had only just opened—nobody knew about me yet.

It was for the TAKE ACTION CHARITY GALA, hosted annually by former Japan national footballer Hidetoshi Nakata to support traditional crafts. Tokuda-san was appointed as a member of the advisory board, and she, Yoshihiro Suda and I collaborated on three art pieces together for the event.

How did the collaboration go?

Our first meeting happened in an unexpected place… a hot spring. Instead of jumping straight into business talk, she said, “Let’s go to Gero Onsen, all three of us.” I was surprised.

There, Suda-san and I soaked in the bath, talking, “Any idea what we’re going to do?” (laughs) But the hot spring was nice and we warmed up to each other for sure.

Did you know Suda-san before?

I knew his name as an artist, of course, but it was our very first time meeting in person. It’s Tokuda’s way: she likes to set up space for everyone to come together. If it were a business meeting in a conference room, I’d probably get a little stiff sharing ideas for the first time. Instead, we soaked in the bath, shared meals, and slowly let ideas flow. By the end of that trip, 80% of the concept was in place.

That being said, turning that idea into a finished work was the hardest part.

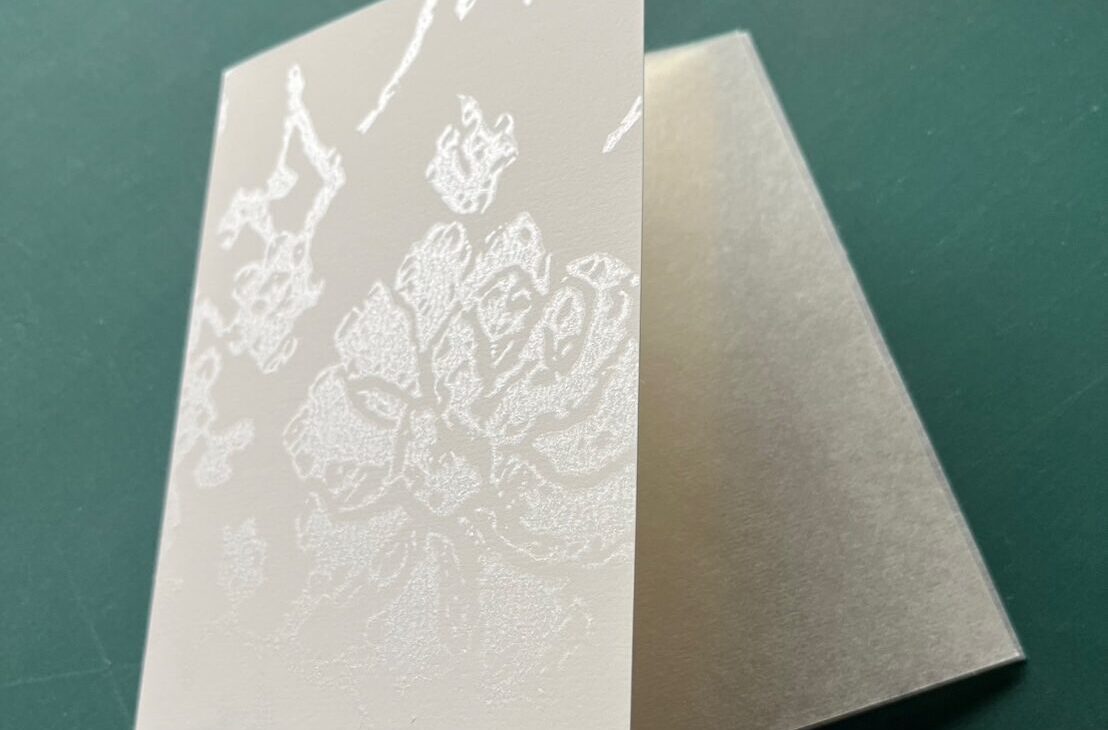

"Snow camellia Tsuitate" ©Junichi Takahashi / TAKE ACTION FOUNDATION

"Morning glory vine Tsuitate" ©Junichi Takahashi/TAKE ACTION FOUNDATION

We created two tsuitate partitions and a pair of furosaki folding screens. Suda-san carved morning glories and camellias for each tsuitate. I printed patterns of morning glory vines and leaves behind the carved blossom so the morning glory would appear to bloom out of the paper. Camellia was paired with falling snow. One pair expressed spring/summer, the other autumn/winter. Working with him was a lot of fun, and good work came out of it.

When do you feel you’ve done good work?

When there is not too much forcing. For example with karakami, instead of trying to reinvent it entirely, you just shift it slightly — and the action brings a fresh perspective entirely. It’s tempting to try out something completely new, like leather or cloth, in an attempt to be innovative, but I prefer simply shifting how traditional fusuma -sliding door- paper is presented.

Even placing it in an unconventional location can give it a new meaning, right? And I enjoy it when that kind of quiet transformation draws people in.

Then again, I must say our work was by far the most subdued at the CHARITY GALA (laughs). People tend to favor flashier pieces at events like that. We were in a completely different lane. And, in a sense, I’m still doing things the same way.

TOMORROW FIELD 2025

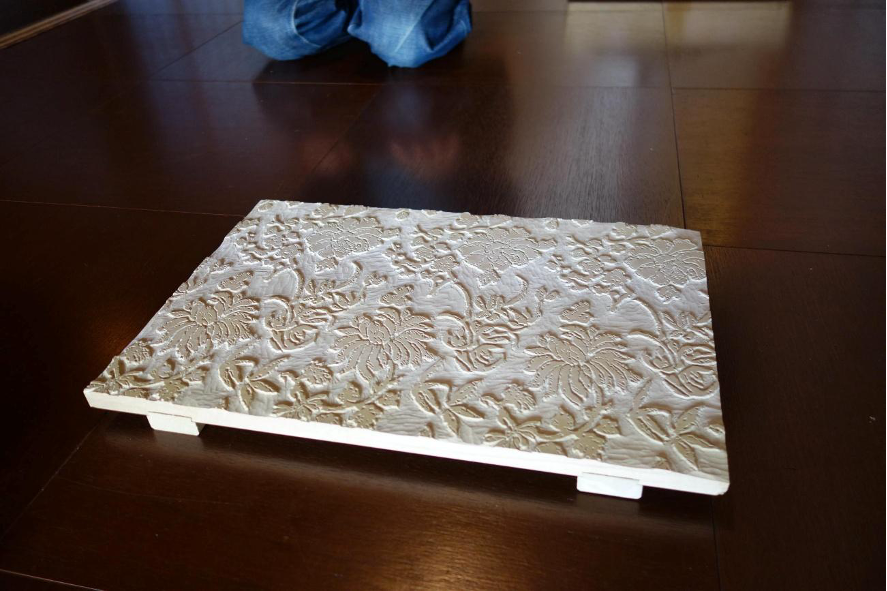

You’re currently working with ONJIUM (Korean cultural heritage research institute) to recreate “Four Gracious Flowers and Peony Patterns” used on a folding screen from the Joseon dynasty. How do you transfer the woven motif to paper?

I reworked the motif data on a computer to fit into the karakami scale. You can’t just use the original pattern as it is, as karakami patterns are handprinted using wood block repeatedly. And each repetition needs to be in alignment with the previous, so the entire work will end up looking like one continuous pattern.

The standardized block size is about 45cm wide. It’s a lot of fine adjustments in order to fit the original motif into the scale — angle, spacing, and proportion. The changes shouldn’t be too obvious, either, as the final pattern needs to retain overall resemblance to the original. This part is the hardest, though it tends to go unnoticed.

People assume it’s just a direct copy of the original design.

Exactly. But behind the scenes, there is much unseen work.

That being said, I want people to see how beautifully the textile motif can be, and is transferred onto paper. That’s what Japanese craftsmanship is about; precise, clean, and proper. I’ll just work my best as I usually do. I believe that’s what ONJIUM team is looking to see, too, so.

Woodblock for the ONJIUM collaboration, which was just delivered during the interview.

A Craftsman’s Standard

How do you choose which jobs to take?

I sometimes wonder if taking on a product development job for a large international corporation could bring me a fortune. But then again, it’d require me to deliver hundreds of thousands of items a month, which is physically impossible.

I could hire people and scale up, but I’m not interested. I want to go deeper into the quality of the work, not broader.

You often say you want to be recognized for your skill as a craftsman.

Yes. I want to be known for my skill and craftsmanship, not ‘taste.’

Skill over Style?

Exactly. Style is subjective. Skill is not.

When it comes to cultural property restoration, for example, no one would say ‘That young fella is doing something interesting, let’s try him out.’ No.

I’ve been through a situation where one day someone pops in and hands me a prototype to make. If they like it, they might come back to give me another. Only if I pass that again, then, do they say, ‘Okay, make the final version,’ which is the order for actual work. They only care and judge by your skill. I like that kind of work.

Once you build knowledge, skill, and experience, your capacity widens and your foundation becomes firmer. So you don’t panic even when an unusual request comes along. But if you rely only on style and not substance, you’re lost when something really demanding comes up.

That’s why I want to work on building a solid base — a triangle with a wide foundation. Then I can take on any assignments.

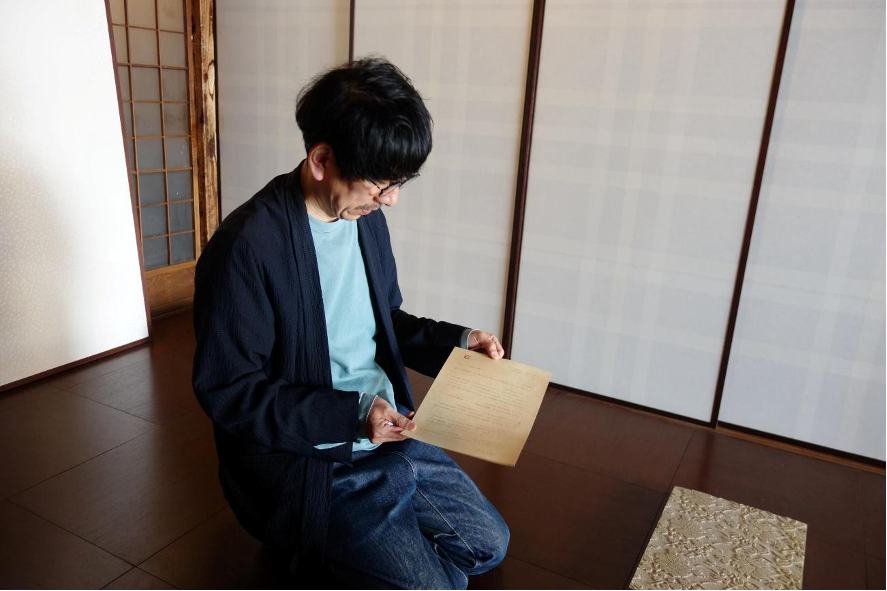

Koh Kado at Kamisoe

Shifting Perspective Without Losing Essence

It’s been 16 years since you became independent. Has your perspective on your work changed?

I wanted to go deeper into classical aesthetics and techniques. So when I started on my own, I started with only painting with gofun (white pigment from ground shells), and when I felt satisfied with the process, I layered it with kira (mica powder) patterns on top. This very traditional process brings out different textures of white in layers, which I think is very beautiful. I kept on doing that all the time. People today find it striking because we’re so used to seeing multi-colored prints. I’d tell them I’m not doing anything new; I’m returning to the basics.

Let’s say in cooking, if you have good, fresh vegetables, you don’t even need seasoning. But if the ingredients are poor, you may need stronger flavoring to mask them. Same with karakami, the simplest way highlights the quality of the material the best: it could be the hardest thing, but my aim is to showcase the quality and beauty of the material without adding anything extra.

So when I say I ‘shift’ things slightly, that’s what I mean. I’m not trying to create sculptural installations from karakami. I simply adjust how it’s presented slightly. That change alone can highlight its original beauty. I enjoy working with people who appreciate that subtlety.

Taiza Paper

Tell us how you found the pigment for the Taiza paper.

Well, technically, it was Hashizume-kun who dug it up.

(Hashizume) We were looking for something that felt ‘Tango-like,’ and we struck this reddish-orange clay. Since ‘Tango’ includes the character for cinnabar or mercury (丹), I thought it was a good match. I sent Kado-san a sample, and it turned out beautifully. But I heard it was a lot of work?

Yes, it was. Cleaning and processing raw soil into pigment, and then reprocessing that into usable paint—it takes time. Cleaning the tools afterwards is a whole other job, too.

But when I saw the finished color and paper… Honestly, it was stunning. I thought, ‘That’s it. My job for TOMORROW FIELD might be done now.’ (laughs) Though the public’s reaction has been a bit lukewarm—I’m not sure why!

Tango fusuma, ECHO, 2022. The fusuma paper finished with the Taiza soil pigment will also appear in the "Papered Room" exhibition this autumn.

The Artist is Kayo Tokuda

You’ve been part of TOMORROW FIELD since the beginning. Is that because you and Tokuda-san share the same vision?

I like what she’s trying to do, though it’s such a tough goal to achieve. But I admire it.

In the end, the artist is Kayo Tokuda herself. I always thought that. She has this vast vision of the world, and we—craftspeople, artists, architects—are brought in to shape that.

At first glance, it looks like each individual work is made by so and so, but in reality, we’re building the pillars that hold up a much larger structure—an environment she envisions as a whole.

The concept of building a cemetery, too. She started mentioning that even early on.

What did you think when you heard that idea?

I thought it was so her.

When I first met her, I thought curators were just people who made exhibitions. But she’s completely different.

She’s created so many amazing works already. And this current project, TOMORROW FIELD, may be the last of its scale. I’m curious to see what comes of it. I may not even be around when it’s complete. But I still want to see what it becomes.

At Kamisoe. Yoshihiro Suda’s sculptural work peeping from the wooden table behind.